Imagine sitting by a rushing river. At first glance, it may seem that only water is being moved from one end of the river to the other, but if you take a closer look, you may see that the water also disturbs the rocks and soil in the river, dragging some of them with it until you cannot see them anymore. There may also be fish and insects swimming in that water’s flow. You might even be joined by a bird, staring attentively at the moving surface, ready to pounce on one of those fish and insects. This connection along a river moves key elements of an ecosystem: nutrients, wildlife, water. For the Amazon, a research team led by Dr. Elizabeth P. Anderson (Florida International University) and consisting of twenty-one authors (ten are partners of the Amazon Waters Alliance) aimed to understand how well this flow connects the Western Amazon[1] to the rest of the basin, publishing a study titled, “A baseline for assessing the ecological integrity of Western Amazon rivers” in Nature Communications Earth & Environment.

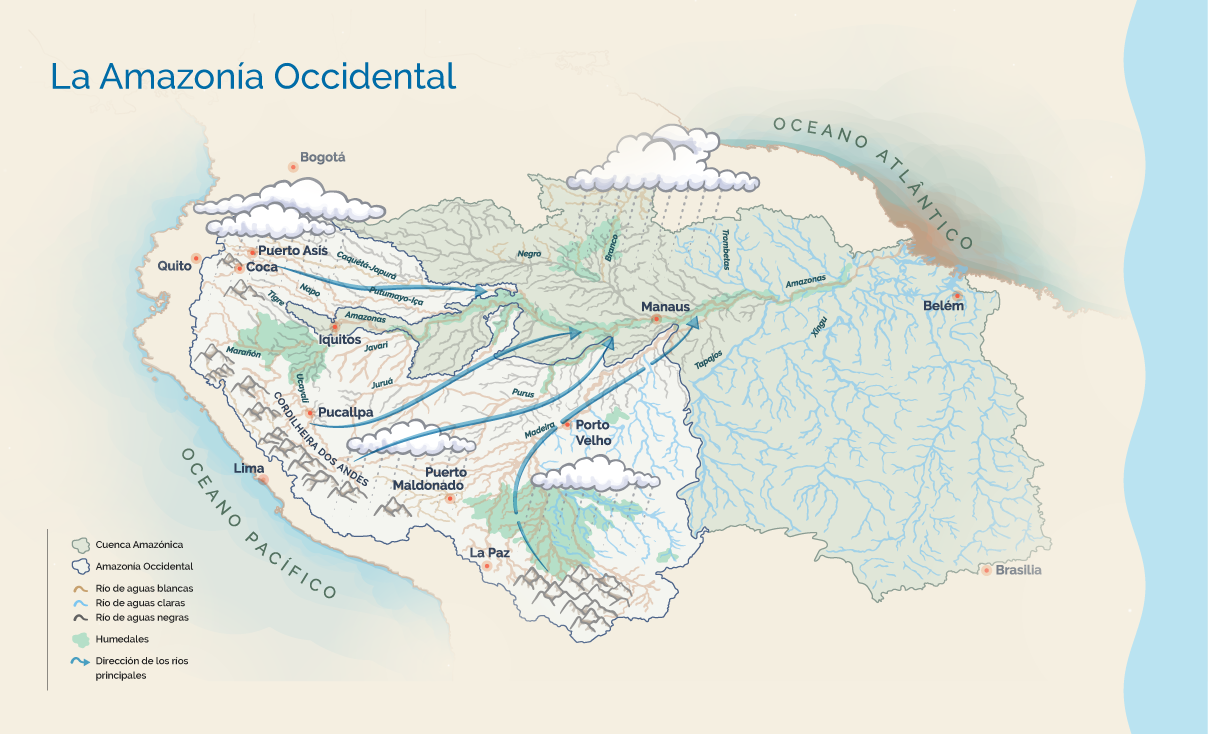

Mapa de la Amazonía occidental. © Alianza Aguas Amazónicas

The study assessed patterns related to hydrology and sediments, freshwater fish biodiversity, and river connectivity along longitudinal pathways, all key components that underpin the ecological integrity of Western Amazon rivers and their linkages to the larger Amazon basin. It also estimated human populations and mapped their location in the Western Amazon relative to rivers. By characterizing these different aspects of the basin, we can measure how things are changing in the future as a consequence of infrastructure development, conservation strategies, or other factors.

Key results in each of the components investigated include

Hidrology and Sediments:

Streamflow of the Western Amazon sub-basins has been largely driven by precipitation. Precipitation is generally highest in the northern tributaries of the Western Amazon, decreasing towards the southeast and in the high Andean elevations. Analysis of the mean annual sediment yield patterns showed that essentially all sediment (>90%) discharged by the Amazon River comes from the Andes. These results highlight that without the rainfall the Western Amazon is used to, water and nutrients that allow for agriculture, biodiversity, and navigation won’t move from the Western Amazon to the rest of the basin. Actions that reduce greenhouse gas emissions, like transitioning to renewable energy, must be taken to minimize climate change effects on the hydroclimatic cycle.

Freshwaters Biota:

1,868 fish species (74% of Amazonian ichthyofauna) have been scientifically documented from the Western Amazon river basins, with the highest number of fish species known from the Madeira, and the lowest in the Javari and Jurúa. The Napo basin has the highest density of recorded fish species. At least 76 of fish species scientifically known from the Western Amazon are longitudinal migratory fish species. The Amazon is one of the most biodiverse regions in the world, and much of it, including many parts of the Western Amazon, has not yet been scientifically studied. This description showcases how with even limited information, the Western Amazon represents the majority of fish diversity in the basin. Additionally, the identification of longitudinal migratory fish species shows that species need well-connected rivers to survive.

Longitudinal River Connectivity:

3,734 road crossings and 396 dams (45.6% of all Amazonian dams) were documented to cross rivers in the Western Amazon. There are an additional 203 proposed dams in the region. Dams were most heavily concentrated in the Madeira, Marañón, Ucayali, and Napo River basins, while the Caquetá-Japurá, Putumayo-Içá, Javari, Purus, and Jurúa basins have no existing or planned dams. Dendritic Connectivity Index analysis, where 100% represents no obstructions in the flow of a river, showed that the Madeira and Marañón river basins have seen the most connectivity loss from the headwaters to the confluence of those rivers with the Amazon river (51% and 70% DCI, respectively). Connectivity from the confluence to the headwaters was lowest in the Madeira basin (31%), due to two large dams upstream of Porto Velho, Brazil, while all other basins had levels above 83% DCI. This baseline of longitudinal river connectivity in the Western Amazon is reason for hope. There is a tremendous opportunity in maintaining rivers free-flowing: by prioritizing this ecological connectivity, we can prevent a huge future cost to society in the form of removing obstacles like dams, as has been shown to be necessary in other countries.

Human Populations:

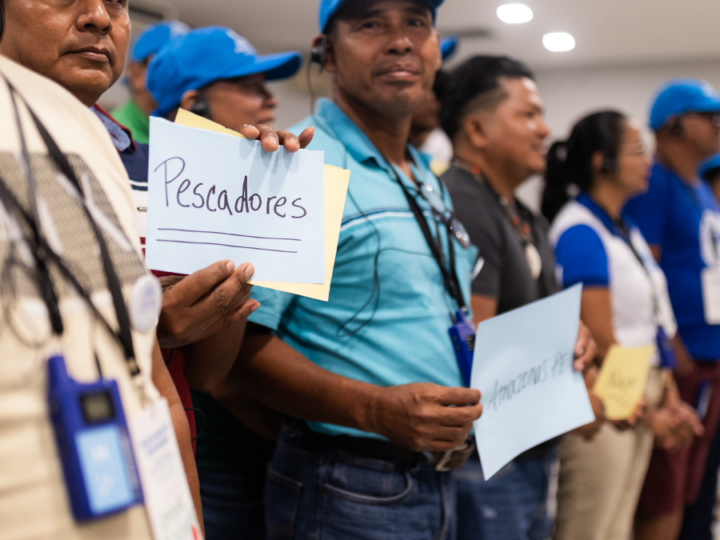

Researchers estimated that 47.8 million people inhabit the Amazon basin, with 58% of the population located in the Western Amazon. Most people are found in the middle and high elevations where there are large cities along rivers or at their convergence. The Madeira basin has the highest human population (10.6 million) with cities like Cochabamba and Santa Cruz de la Sierra, Bolivia, and Porto Velho, Brazil. The rivers of the Amazon basin hold important economic and cultural values for riparian human populations, including as a source of nutrition and income (via fisheries and agriculture), as a way to navigate and communicate between human settlements, as a spiritual basis for the worldviews of numerous Indigenous groups, and as a rhythm that organizes social activities, such as festivals, celebrations, and even school. Given the importance of river connectivity to the diverse and unique social-ecological systems in the basin, riparian human communities have many reasons to care for maintaining this connectivity and should be empowered to lead in conservation strategies.

Fishing in the Western Amazon, Peru. Photograph: Diego Pérez © WCS

Imagine you are back at that rushing river, except this time, it is barely rushing. There is now a dam and the river has been backed up to create a reservoir. Sediments and nutrients are stuck on one side of the dam, while the other side of the dam has fish that can no longer reach the places where they reproduce. In the Amazon, without dams, sediments and nutrients from the Andes can make it all the way to the Atlantic Ocean! The researchers of this study suggest a variety of conservation and planning strategies that maintain freshwater connectivity, including basin-scale and multiobjective approaches for planning infrastructure developments, recognition of Western Amazon river corridors as objects of conservation, and establishment of transnational fluvial reserves that protect and remove certain rivers from consideration as locations for large infrastructure projects. This baseline can be a foundation for making and evaluating conservation decisions connected across national boundaries. The Amazon Waters Alliance builds on these recommendations: Riparian human communities must play a leadership role in the design, implementation, and management of these conservation strategies. When communities that depend on strong relationships with their surroundings are in charge of conservation, we have seen better outcomes. Dams obstruct not only rivers, but these strong relationships. For this reason, AAA calls for maintaining the free flow of healthy Amazon rivers.

_________

1 The Western Amazon includes the Caquetá-Japurá, Putumayo-Içá, Napo, Marañón, and Ucayali rivers, as well as the Madre de Dios, Beni, and Mamoré rivers of the upper Madeira basin.